Report: Habeeba Al-Hussawi, Mohammed Mutahhar

Graduates of media departments at Arab universities have long suffered from restrictions that hamper them upon entering the journalistic labor market. These restrictions have been a topic of discussion at all previous ARIJ annual conferences, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

This year's conference is held under the title: # Journalism without restrictions, in Early next December In Amman, the question remains: What is the future of graduates in Arab press syndicates? Is digital security still a concern for journalists since the Pegasus hacks? How will female graduates find themselves after graduation, given the growing phenomenon of sexual harassment that has prompted regional and international organizations to call for the protection of female journalists? The most important question of all remains: Why are some journalists left in conflict and war zones without professional support from the media outlets that employed them, and without legal protection from countries that guarantee the right to access information?

These are questions that media graduates are waiting for answers to before they get into trouble that could end in death or ruin their career prospects.

Under strict conditions

Journalists' unions are an essential part of the media ecosystem, playing a significant role in regulating the profession and protecting the rights of journalists. However, there is a clear discrepancy between the policies of Arab and foreign journalist unions regarding granting membership to and supporting new journalists, as well as protecting female journalists from harassment while performing their duties.

In the Arab world, journalistic unions have strict membership requirements. These unions also often impose bureaucratic obstacles that make joining them difficult for new graduates, especially in the absence of sufficient professional support, as is the case in Egypt, which has been a leader in the world of journalism since its inception, where it is necessary for... Graduate journalists Providing proof of employment for a specific period in accredited media institutions to obtain membership.

In contrast, foreign press unions, such as National Union of Journalists in BritainWith more comprehensive and flexible policies toward new journalists, including freelancers, these unions provide training resources and comprehensive legal and professional support, which contributes to strengthening journalists' careers. Furthermore, foreign unions focus on protecting journalists from various violations, including harassment and threats while performing their duties.

And between Arab and foreign unions, it sought Arej To bridge this gap by providing training resources and legal advice to all beneficiaries, both male and female, of journalists in the Arab world, given the scarcity of Arab regional organizations concerned with journalism affairs in general.

In the face of threats

In 2016, I raised Gretchen CarlsonFox News anchor, lawsuit against its CEO, Roger Ailes, on charges of sexual harassment. This case led to Ailes' resignation and the channel's $20 million compensation. The broadcaster's case sparked a major debate about harassment in the American media, helping to shed light on similar cases faced by many female journalists in the United States. Meanwhile, Carlson's doppelgangers exist in the Arab world, with no one responding.

Female journalists face physical and psychological threats, most notably harassment while performing their duties in the field or at work. The Arab world is no stranger to this phenomenon, where they are subjected to it with impunity. The stories of some female journalists provide tragic evidence of this, despite the distance between them in time and place.

Some of these cases have forced many of them to leave the media field or change their career path, in light of modest efforts to protect them, whether at the level of civil society organizations, or the government agencies concerned with protecting them. In Western countries, we find the American-originated MeToo movement contributing to raising awareness about issues of sexual harassment, and it is matched by the “I will not remain silentIn the Jordanian ARIJ network.

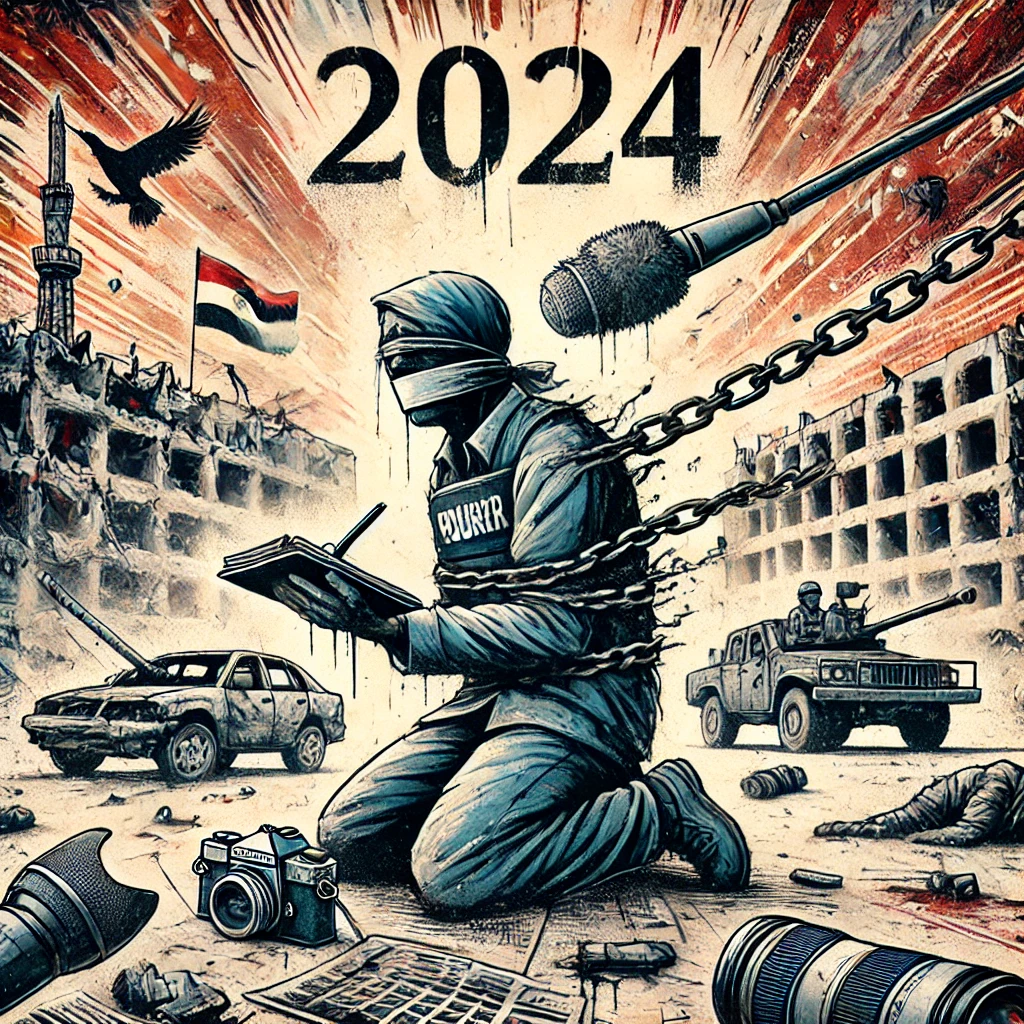

In the heart of the cannon

Journalists in conflict zones face a variety of risks, including physical, psychological, and legal. As is the case in Gaza, more than 174 journalists have been killed, according to the Office. Government media in GazaIn a strong precedent for violating the rights of journalists, without accountability or punishment for their killers, on the one hand, and without any rights being preserved for them after their death, as some of them are considered the primary breadwinners for their families, a situation that is also the case in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq.

Occupational safety is a priority for journalists working in conflict zones, requiring specialized training on how to operate in dangerous environments, including first aid and escaping areas experiencing armed clashes.

Modest efforts to protect them by international organizations such as the International Federation of Journalists, which adopts legal prosecutions of criminals against the press, and the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) network launched... Financial donation window For the benefit of journalists in Palestine.

Even those who have been spared physical assault are not immune to digital hacking, especially since a software company in the Zionist entity granted the “Pegasus” spyware to hack into journalists’ devices, which contributed to the killing of some of them, and the leaking of sources for others, in light of the almost complete absence of confronting this challenge from journalists’ unions, except for what the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) network did by launching the “Safety firstAnd made it available via the WhatsApp quick chat service to serve the journalism community.

Amid this tragic state of affairs for journalists, many graduates, both male and female, may find their future in the profession a death knell, amidst the international silence surrounding the crimes committed against them. This will see the future of journalism gradually recede. Will 2025 be a good omen for journalism and its practitioners in Arab countries, or will it be a sign of an unforeseeable decline?